Ohio Progress Update - Addressing Secondary Traumatic Stress and Providing Supportive Supervision

Secondary traumatic stress (STS) refers to the experience of people – generally professionals– who are exposed to others’ traumatic stories as part of their work. As a result of this exposure, these professionals can develop their own traumatic symptoms and reactions. Child welfare staff are particularly susceptible to STS because of the vulnerable nature of the families they work with, the unpredictable nature of their jobs, and their general lack of physical and psychological protection (ACS-NYU Children’s Trauma Institute, 2011). As such, STS can mimic the symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (Bride, 2007) including nightmares, sleep disruption, avoidance, and irritability. STS in child welfare has been linked to low rates of job satisfaction and staff retention.

The Ohio Department of Job and Family Services (ODJFS) partnered with the Quality Improvement Center for Workforce Development (QIC-WD) to address issues such as job satisfaction and staff retention within the child welfare workforce. Ohio’s child welfare system is county administered and nine counties are participating in the QIC-WD project.

The QIC-WD conducted surveys with 588 Ohio child welfare workers in early 2018 and found that the organizational culture and climate across all participating counties was above average in rigidity and resistance, and below average in engagement. In addition, 53% of respondents had recently experienced elevated levels of STS symptoms. The root cause analysis to determine why agencies were rigid, staff were resistant and unengaged, and most staff were experiencing high levels of STS symptoms, zeroed in on issues related to supervision. Supervision was a challenge at every level from directors to managers, managers to frontline supervisors, and supervisors to frontline workers. To better understand the needs of supervisors the QIC-WD conducted 12 focus groups with 90 frontline supervisors across the nine participating counties in July 2018. The focus groups determined that supervisors wanted:

- More skills in how to coach, give feedback, and support staff

- To increase what they learned in supervisory core training

- More time to be with other supervisors

- To carve out time to engage in supportive supervision, not just casework

- More support from management to support caseworkers

- To improve engagement in practice with clients

It was also determined that frontline workers needed to:

- Develop stronger coping skills

- Take emotions out of the work

- Learn to complain effectively

- Learn how to self-regulate emotions and maintain healthy boundaries (self-care)

- Gain independence and confidence faster

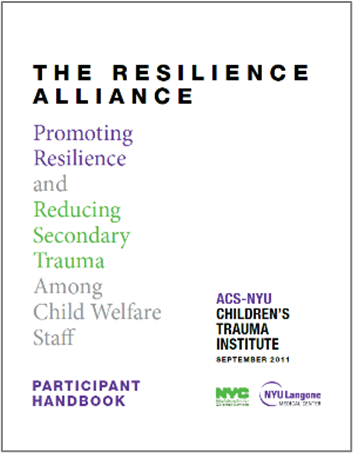

- RA was developed by the ACS-NYU Children’s Trauma Institute to mitigate the effects of STS, create a healthier work environment for child welfare staff, and to help staff develop skills and behaviors that improve their well-being, increase job satisfaction, and reduce turn-over. Frontline caseworkers participate in RA groups facilitated by trained facilitators for 24 weeks and practice these skills in between sessions with the support from their supervisors. Supervisors participate in RA groups with other supervisors to gain coping skills, obtain social support from their peers, and learn what their staff are learning to further support their growth.

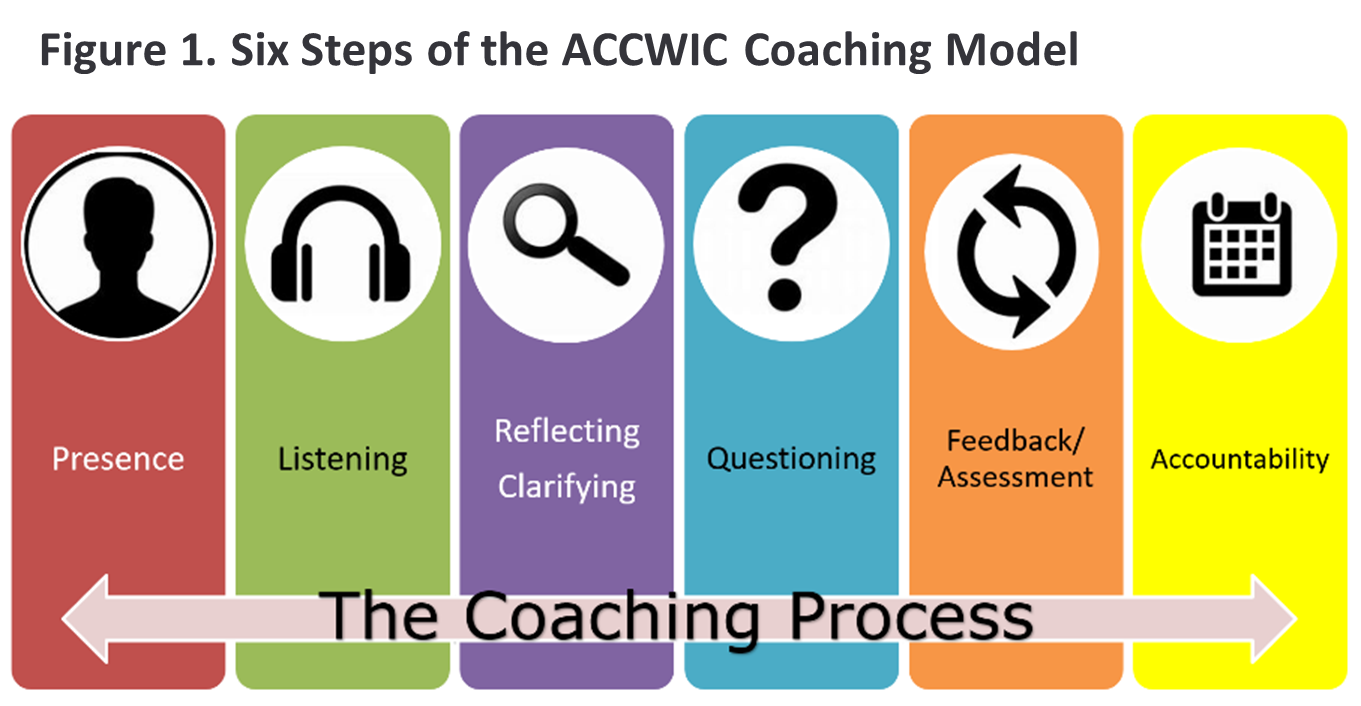

- The Coaching Model, developed by the federally-funded Atlantic Coast Child Welfare Implementation Center (ACCWIC), consists of six steps: being present, listening, reflecting and clarifying, questioning, giving feedback, and holding staff accountable (see Figure 1). Supervisors learn the ACCWIC Coaching Model and how to use coaching to support acquisition of RA skills of their staff.

The multi-level Supportive Supervision intervention called for directors, managers and administrators to be aware of the results of the assessment process and how the intervention would address the issues, while also understanding the parallel process of modeling positive managerial and supervisory skills for frontline supervisors and caseworkers. In addition, directors and administrators would serve as champions for the project by gaining the skills of coaching and supporting supervisors.

Implementation of Coach Ohio began in 2019 when supervisors were trained in the coaching model and practiced coaching skills and the first round of RA groups were delivered. In 2020, counties planned and implemented follow-up RA groups for those who completed the initial 24 weeks and some counties began a second wave of RA groups for those not in the first wave and for new hires. Early reports from participants indicate that managers, supervisors, and caseworkers participating in RA learned how to:

- Cope better with the stress of the job.

- Be more resilient, optimistic, and regulate emotions as deal with the trauma they are exposed to.

- Have more empathy for co-workers.

- Build more supportive relationships with co-workers.

- “RA has been a game changer.”

- “RA provides a safe place to connect.”

- “Resilience Alliance was wonderful...our groups were phenomenal.”

- “What I gained the most was just the self-reflection piece. Looking back and being like, okay, there's multiple ways I can think about this. Let's think about why I'm feeling this way and kind of working with that. That was a huge thing for me and just realizing that maybe I wasn't doing that as much as I thought - I think that helped me the most.”

- “It really professionally changed me, health wise, changed me and there are times when I am frustrated or upset and I handle it completely, completely different. So it taught me some skills that I have to work on.”

- “We would say, ‘let's encourage and promote self-care’, but we were not taking any steps. We're getting all this trauma training about how to interact with our families. But we weren't doing a lot of work around vicarious trauma...but now we're taking a step in the right direction.”

- “It created that teamwork environment from the top down…People really helping each other utilize that hour for self-care and detach and unplug from the work and seeing people encouraging each other to do that, which was really awesome.”

- “I think it's an important piece of employee mental health at this point...I think it is important for the mental health of the agency.”

Results from the rigorous evaluation that compares intervention counties with comparison counties will be available from the QIC-WD in 2021 after a second round of follow-up surveys are administered and administrative data is analyzed to examine impact of the various phases of the intervention on short-term and longer-term outcomes. Short-term outcomes include emotional regulation, optimism, resilience, coping, perceived support, STS, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and intent to stay. Medium- and long-term outcomes include turnover and child outcomes of safety, permanency and well-being.