Perspectives on Multi-Intervention, Multi-Design Evaluation for the Child Welfare Workforce

The QIC-WD is working with eight sites and the Children’s Bureau in a participatory fashion (Fetterman, 2014) to implement utilization-focused (Alkin & Vo, 2017; Patton, 2008) site-specific and cross-site evaluation strategies. The goal of this research is to build knowledge of interventions to improve child welfare workforce retention, and ultimately outcomes for children and families. A complex systems approach (Westhorp, 2012) is being taken to identify how factors such as organizational structures and culture, staff workload, supervision, and caseworker values influence outcomes, including safety and permanency of children.

The QIC-WD team has extensive experience conducting rigorous evaluations within and across multiple agencies. Four common challenges to addressing complex issues inherent in this child welfare workforce research emerged as the team designed its evaluation strategies.

Challenge 1: Lack of integration between Human Resources (HR) and program operations in many child welfare agencies

Challenge 2: Measuring impact within and across sites

Challenge 3: Context dynamics and multiple/competing initiatives

Challenge 4: Varying agency capacities and the unique nature of existing data systems

This blog post describes the strategies the QIC-WD is using to conduct real-world evaluation in child welfare agencies and address these challenges.

Solution: Bring HR to the table to solve child welfare workforce challenges

The QIC-WD has found that HR leaders, staff, and data are often not well integrated into child welfare agency workforce development processes. As a key component of the workforce development process, the QIC-WD teams worked to bring HR to the table. Specifically, HR leaders were included as key stakeholders in needs assessment, intervention, measurement, analysis, and reporting processes. This encouraged more informed decision making on the part of agencies and our team, while supporting more efficient integration of key HR data with other sources (e.g., child welfare).

“[Our] child welfare division was in a larger agency ... that had more than 4,000 employees….in the big agency H.R. was not a strategic partner. It was just too big to be able to become a strategic partner, not that they didn't try.” – QIC-WD Site Implementation Team Member from HR

Solution(s): Use common measures, compare effect sizes, and take advantage of natural variation

Research and evaluation projects commonly face challenges that could impact the validity of findings. These challenges are compounded in the multi-site context. The QIC-WD has confronted potential threats to:

- Implementation fidelity – when interventions to improve the workforce are not conducted as originally intended. For example, when an agency does not use new procedures designed to identify the most appropriate hire for a position, because they have not trained hiring managers to properly implement them; or when caseworkers do not delegate administrative paperwork to the team members whose job it is to handle it under a new job redesign model.

- Measurement fidelity – when the same measures of the workforce are not implemented, or implemented in the same way, every time. For example, when surveys of workers in different agencies ask different questions intended to address the same topic.

- Design validity – when a major event external to a workforce study has direct and unmeasurable impacts on the study. For example, workforce changes such as working remotely due to COVID-19 have changed the nature of some QIC-WD research.

- Measurement validity – when observations of the workforce do not measure what was intended. For example, when measures of worker stress are actually measuring stress imposed by life changes due to COVID-19, rather than stress caused by work per se.

One strategy to navigate the challenge of measuring impact within and across sites it to use common measures and administrative data. Common measures may be gathered through survey data or observations to capture identical data points from multiple jurisdictions, regardless of the intervention. Similarly, administrative data (i.e., data collected in the jurisdiction’s HR or child welfare system for program administration purposes) has common variables that can be examined consistently across sites. These data sources are used across research sites to allow for investigation of the extent to which interventions and measures were implemented reliably. They provide points of comparison within and across sites and experimental groups. Similarly, use of common measures and administrative data support statistical comparisons within and across sites and experimental groups, to provide insights about the relative impact of interventions.

Common measurement across project sites will also allow for the comparison of effect sizes. Measures of effect reveal the strength and type of relationships between various hypothesized causes (e.g., organizational qualities, workforce improvement strategies, contextual factors) and key outcomes (e.g., turnover and consequences for children and families). How the strength and type of relationships vary across sites can reveal the extent to which different organizational circumstances or workforce interventions impact turnover. For example, how child welfare agency staff react to work changes due to COVID-19 may impact turnover differently across sites. In this example, measures of effect size can provide valuable insights about how interventions to reduce turnover (i.e., job redesign) may work under conditions of great stress and rapid change (i.e., a pandemic).

Another strategy to measure impact within sites is to leverage naturally occurring variation in intervention implementation. Measures of the implementation process can: (1) guide development, (2) reveal where implementation has gone awry, (3) support identification of advantageous intervention innovations or adaptations, and (4) provide context for analysis and interpretation of outcomes. Where variations exist due to local circumstances, such as the pivot to remote work due to COVID-19, careful documentation of the implementation process can extend our understanding of what elements are key to achieving desired outcomes and how various adaptations affect them. For example, time studies in one of our sites confirmed that caseworkers involved in a job redesign to strengthen the child welfare workforce were able to continue teaming despite working remotely as a result of the pandemic.

Solution(s): Track key events that impact the workforce (“site chronicles”) and manage risk

The context in which child welfare agencies operate is important for understanding workforce development and the types of interventions the QIC-WD is investigating. Issues such as politics (e.g., leadership changes), law and policy (e.g., changes in agency mandates, guidelines, or practices), economics (e.g., income distribution and unemployment), health (e.g., COVID-19), social changes (e.g., social justice demonstrations), and others may all bear on how and to what extent workforce interventions are effective. To monitor and document such dynamic changes to the study environment, the QIC-WD implemented “site chronicles,” a survey/diary tool to capture the date and character of events of significance to the workforce. Child welfare agency team members routinely report the details of factors in the local environment, such as a change in leadership or practice, that may impact the workforce in the site chronicle (see Figure 1). This data is being captured (and therefore can be compared) across all sites.

QIC-WD research teams have also worked with sites to manage risk to these studies. Risk management involves identifying threats to validity, assessing the likelihood of threats occurring and their severity, assigning a risk score to rank them, creating plans to manage risks in the event they occur, then periodically updating the process. This has allowed research teams to be prepared for challenges such as the need to train new staff and supervisors on the requirements of a job redesign and teaming model as existing staff leave.

Figure 1. Chronicle (Sample from Sept. 2020)

Solution(s): Data coordinator, administrative “data shells” and Extract, Transform and Load (ETL) tools

Another challenge faced by the QIC-WD research team is the varying capacity of child welfare agencies to manage administrative data and the unique nature of their existing data systems. Data about workforce issues are often held in disparate locations, forms, and may suffer from quality concerns. The QIC-WD recognized the necessity of designating an individual embedded within the agency who would be responsible for facilitating the extraction, matching, and transfer of child welfare and HR administrative data essential for the research. Thus a “Data Coordinator,” with knowledge of agency data systems and the positional authority to facilitate the work, was identified (and financially supported by the QIC-WD) in each of the project sites.

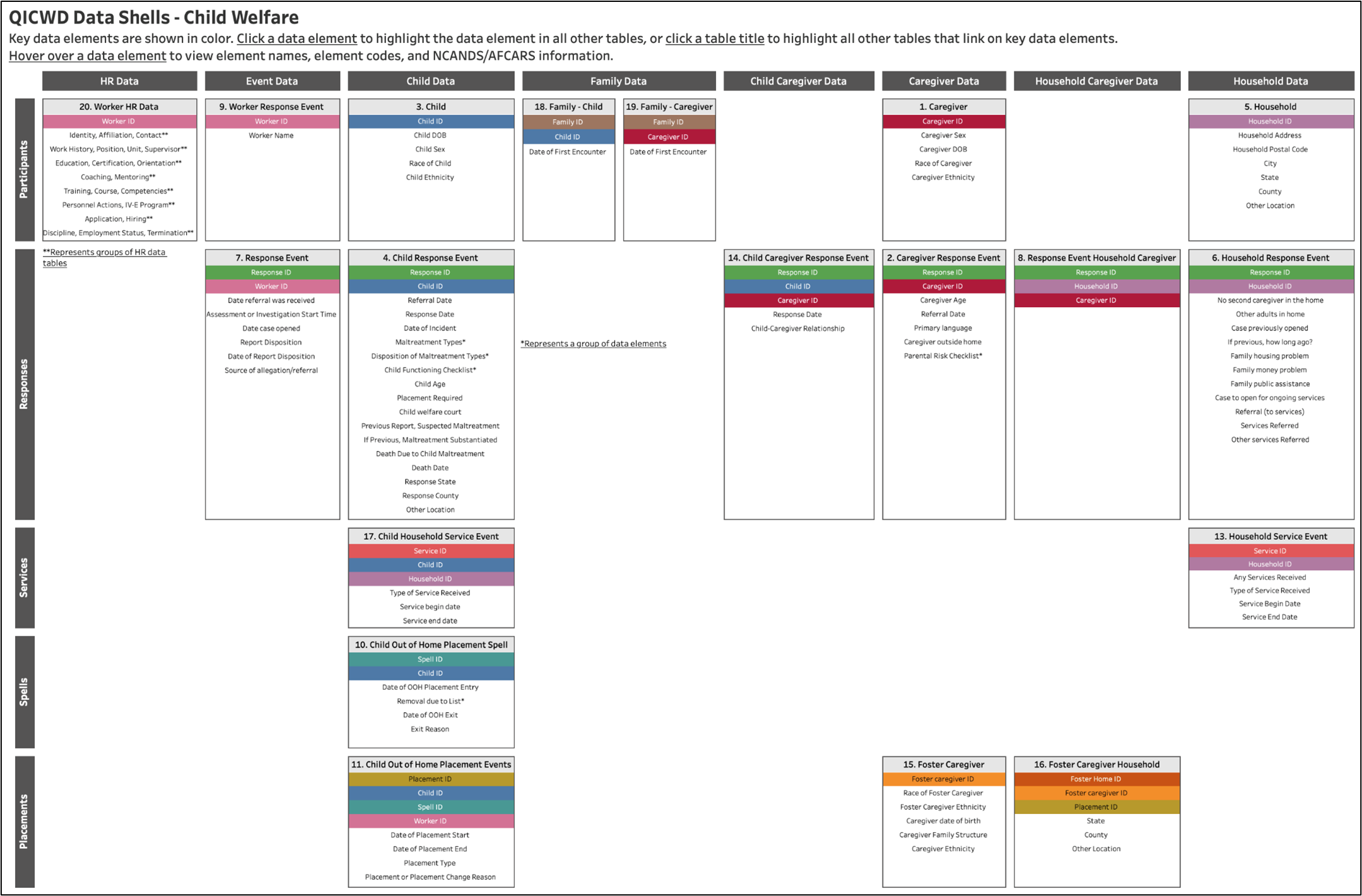

To address the limitations of and variations in existing data systems the QIC-WD developed “data shells” (see Figure 2). Data shells provide a common structure to guide extraction, organization, and linking of data to produce measures from a series of HR data elements (such as employee ID, office name, position ID, start date, highest education level, licenses, and training) and child welfare elements (such as worker ID, case assignment date, and supervisor ID) that can be used to analyze HR and child welfare data to answer pertinent workforce questions.

Data shells guide the QIC-WD evaluator and agency partners to identify the types of child welfare and HR data available for analysis, and catalog differences in available existing data within and across sites. These efforts have provided the research team with information necessary to use Extract, Transform and Load (ETL) tools (software that allows you to pull data from various sources, prepare the data for analysis, then export the data in any format for efficient analysis or sharing) to efficiently bring together existing data from disparate sources within each study site, as well as synthesize common data types across sites, which are both essential components of any multi-site research and evaluation project.

Researchers at the QIC-WD are adapting and testing tools to address common workforce evaluation challenges. Facilitating data sharing and communications between HR and child welfare leaders, measuring common indicators across sites, and capturing contextual changes in jurisdictions are strategies the QIC-WD is using to evaluate child welfare workforce development interventions. This multi-site, multi-intervention, multi-design evaluation requires innovative evaluation strategies to gather data from multiple systems (e.g., HR and child welfare) in multiple formats (e.g., surveys, observations, chronicle entries) to answer critical questions about what works to support workforce development in complex, real-world child welfare systems.