Recent Research to Build Knowledge of the Child Welfare Workforce

Child welfare worker turnover is costly and can negatively affect the relationship between families and the child welfare agency. The Quality Improvement Center for Workforce Development (QIC-WD) aims to build the body of evidence in the child welfare field to better understand worker turnover and strategies to address it. Although turnover is a widely acknowledged problem, there has not been reliable data to calculate staff turnover, caseloads, and workforce capacity. A recent study and article, Characteristics of the Front-line Child Welfare Workforce (Edwards & Wildeman, 2018), makes available a new data source and provides an analysis of workforce data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) data files (data is from 46 states, 2003 to 2015). This data set is valuable because it allows researchers to use standardized measures of critical issues (i.e., staff tenure, staff turnover, caseloads, and workforce capacity) and to compare these measures across states. The QIC-WD is using this article to inform and shape some aspects of our evaluation. This blog post highlights some interesting findings from the article and discusses how it complements our work.

Child welfare worker turnover is costly and can negatively affect the relationship between families and the child welfare agency. The Quality Improvement Center for Workforce Development (QIC-WD) aims to build the body of evidence in the child welfare field to better understand worker turnover and strategies to address it. Although turnover is a widely acknowledged problem, there has not been reliable data to calculate staff turnover, caseloads, and workforce capacity. A recent study and article, Characteristics of the Front-line Child Welfare Workforce (Edwards & Wildeman, 2018), makes available a new data source and provides an analysis of workforce data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) data files (data is from 46 states, 2003 to 2015). This data set is valuable because it allows researchers to use standardized measures of critical issues (i.e., staff tenure, staff turnover, caseloads, and workforce capacity) and to compare these measures across states. The QIC-WD is using this article to inform and shape some aspects of our evaluation. This blog post highlights some interesting findings from the article and discusses how it complements our work.

Child welfare workers and supervisors have difficult jobs. They leave for a variety of reasons related to the job including the hours, the administrative burden of documenting their work, the demands of their caseload, and the constantly changing work environment. The QIC-WD is working with eight different child welfare jurisdictions to address a variety of the causes that can lead to turnover. We are also accumulating and summarizing the available research that describes the characteristics of the child welfare workforce and available strategies to address turnover. The Edwards and Wildeman (2018) study presents several interesting findings about the workforce, highlighted below.

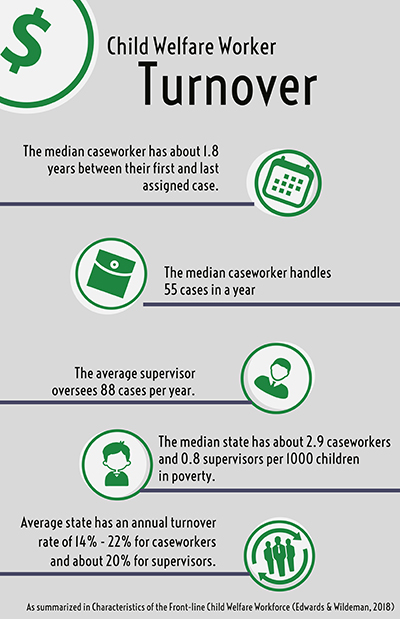

- Turnover: The median caseworker has about 1.8 years between their first and last assigned case. Furthermore, half of supervisors were in that position for less than 2.5 years. Study authors, Drs. Edwards and Wildeman, estimate that an average state has an annual turnover rate of 14% - 22% for caseworkers and about 20% for supervisors. Seventeen (17) states have annual worker turnover that is greater than 25% of their workforce.

- Caseload size: Some child welfare workers have an annual caseload of about 19 cases or less, while others had a caseload of 97 cases per year. The median caseworker handles 55 cases in a year and 10% of the caseworkers identified in the NCANDS files had a caseload of more than 130 cases per year. The number of cases supervisors oversee also varied across states, with the average supervisor overseeing 88 cases per year.

- Capacity: The median state has about 2.9 caseworkers and 0.8 supervisors per 1000 children in poverty. The range is from about 1.2 to 12.5 caseworkers and about 0.5 to 3.7 supervisors per 1000 children in poverty. The number of children in poverty is a proxy for those who are “at-risk of becoming a victim of child abuse or neglect.” These calculations are used as a measure of organizational capacity to respond to child maltreatment.

All the jurisdictions that applied to be part of the QIC-WD were concerned about the turnover among their child welfare workforce, and what that means for the families they serve. The QIC-WD selected six states, one county, and one tribe to participate in the QIC-WD study; five of the QIC-WD states are included in the Edwards and Wildeman (2018) study. Four of the five QIC-WD sites in the study were among the 17 states with an annual worker turnover that was greater than 25% of the workforce. This study did not calculate turnover using the same formula as the QIC-WD, yet the turnover rates were similar. This study confirms the level of need among many states and finds it is possible to calculate workforce trends from NCANDS data.

The study authors note that the data are imperfect and that certain information could not be ascertained from the NCANDS data, however, they acknowledge, and we agree, that these data provide new opportunities to continue to build our collective understanding of the child welfare workforce. The work of the QIC-WD, and future studies that use this data set, can explore research questions about workforce stability, the effectiveness of staff recruitment and retention efforts, and the impact of staff turnover on children and families served by the child welfare agency.